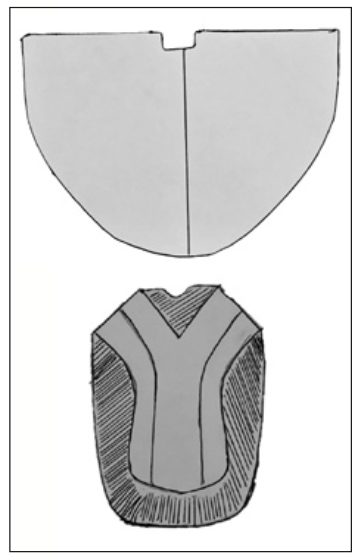

The chasuble has evolved from a full circular garment, to narrowing of the sides, to the fiddleback chasuble

What? The whims of fad and fashion enter the church? Sure, did and does. Even in the church, styles change with passing centuries and the adaptations needed to perform the liturgy. To this day, some denominations require a particular vestment while others do not. Some require the retention of 16th century decoration, others allow a more contemporary approach, including accommodating the clergy’s personal design preference.

Specialized liturgical clothing did not come from First Testament dress [read segments from Exodus 28-39 for those descriptions], but from local custom, from Greek and Roman government and military dress. The early church people did not want to be singled out as Jesus’ followers by dressing differently from their neighbors; so, when they gathered, each wore their newest or cleanest outfit made of wool or linen, bleached by the sun. Even within their church community, all wore similar clothes as there were no distinctions between leadership and laity. If it was sunny, the clothing was the flowing, narrow-sleeved, long middle eastern dress we still seen on men today. This garment became today’s alb, through many adaptations tried over time. Often this was topped with a circular cape which protected against the rain. Should it be cold, then a hooded poncho-like garment was worn, which became the cope.

In those early centuries, church leadership began to develop, separating leadership from laity: subdeacons, deacons, priests cardinals, bishops, popes, abbots and abbesses. Distinct clothing for specific jobs was tried, discarded, tried again; some were retained until the 5th or 6th centuries when a real distinction between secular and religious dress arose.

“Why?” you may ask. The mantra, “We’ve never done it that way before,” must have started when Germanic tribes conquered Rome. The invaders wore pants and tunics…horrors! Secular society adopted these newfangled outfits, which made it easier to ride a horse, go to war, or farm. Stubbornly, the church retained its robes, which began to show status through shape, decoration, and color as various levels of leadership adopted its own particular garment. When Constantine made the church public in 313, there was no need to keep church affiliations secret; as church architecture became more elaborate so, too, did vestments.

Yet, the tension between what to wear or not continued into the early Middle Ages. Pope Celestine I [c 425] said bishops must be distinguished from people by learning, not by dress, by life not by robes. This debate between separate and same continued until 1200 when vestments were standardized.

In 725 [Council of Ratisbon] the chasuble [once a raincoat] became the required Eucharistic vestment. As it was easier to raise the arms when holding up the chalice and paten, it went from a full circle of heavy fabric to a narrowing of the sides, to the lighter weight fiddleback chasuble. In the 9th century priests had their backs to the congregation (it wasn’t until the mid-1900s that they faced the congregation again) and, thus, the backside of the chasuble became highly decorated, the under alb had decorative sleeves and hems, the stole entered the vestment domain, based on a long scarf used to keep noses warm.

In the late Middle Ages, the English church became a leader in the decoration of vestments with gold metal threads [Opus Anglican]. Most embroidery was ‘educational’ with depictions of saints, angels, scenes from Jesus’ life and Mary’s. Fabrics were sumptuous: velvets and heavy silks with linen underlays to help support the weight of the embroidery. Other vestments enter the church by the 1100s: tunicle, dalmatic, orale [short shoulder cape], miter. Some were kept, some discarded.

In the next issue of Epistle, we will cover from the Reformation onward.

About the author: Marylyn Doyle, an ordained minister in the United Church of Christ, taught textile art for 23 years at Union Theological Seminary in Dayton, Ohio. She has shared her vast knowledge of the history of vestments, as well as teaching embroidery and needlework in seminars across the country with all denominations.

History of Vestments (Part III): The Future « National Altar Guild Association says:

[…] Click here for “History of Vestments I: Early Church to Middle Ages” and “History of Vestments II: English Reformation to the 21st […]